A friend just let me know about the fantastic and fascinating article "Japan in Japan: Notes on an Aspect of the Popular Music Record Industry in Japan," by Toru Mitsui (Popular Music, Vol. 3, Producers and Markets (1983), pp. 107-120). It's a detailed and well-informed description of, first, Japanese labels' practices in the late 1970s and early 1980s with regards to the import of foreign records, and second, of the popularity of the English band Japan in the early 1980s. Though of course not quite current, it's a great window into the subtle processes that can dictate how culture travels between modern societies.

What Mitsui primarily focuses on is the fact that by the 1970s, bidding wars between Japanese labels had made artists already well-known in the West progressively less profitable as higher and higher royalties and advances were promised. This led to Japanese labels more aggressively scouting unknown international talent, who still held a broad appeal for the Japanese market. Particularly interesting to me is that Japan were essentially an art-rock band, but they managed to attract a teenybopper audience in Japan because of their heavily made-up, androgynous image. This audience supported them through three early albums that didn't sell particularly well in England or America. David Sylvian, once a member of Japan, is now one of the leading avant-garde musicians in the West, a position he might not have achieved without the financial support of the Japanese market.

Cases of bands not popular in their home turf succeeding wildly in Japan are so common they've become a cliche. Mitsui cites the early success of Kiss in Japan, and the paradigm case is the band Mr. Big, who are essentially unknown in the West but still tour incessantly in Japan.

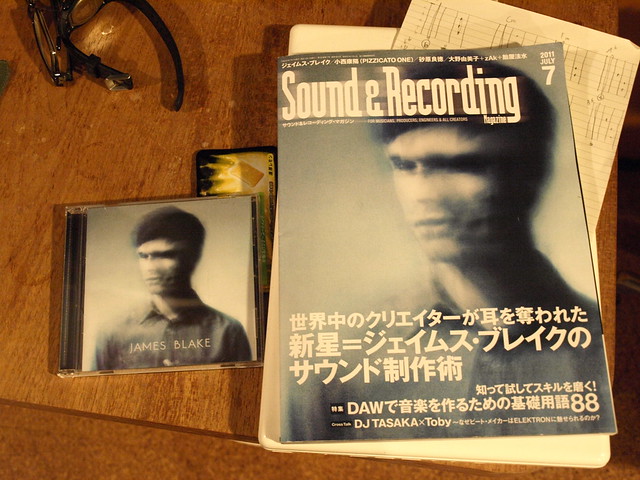

More recently, there's the case of James Blake. My general impression is that while he's become quite well known in the U.K., he's definitely a niche product in the U.S., pushed by fringe indie websites like Pitchfork and Gorilla vs. Bear. In Japan, while still not a star, his extremely bleak and fairly abstract album has reached the 70th spot on the Oricon album charts since its release about six weeks ago (I'm really wishing I had a full Oricon subscription right now). According to an interview with Ele-King, his import singles were selling out back in February, the kind of thing that builds great buzz for a domestic release. That qualifies him to represent a sort of indie/underground version of the more thoroughly dominant, but also clearly more straightforwardly marketable, likes of Kiss and Mr. Big.

|

| Courtesy Kishimen |

It's not entirely clear why or how this happened. He's backed here by the Universal International label, but there aren't overwhelming signs of where that power is going. He's had prominent listening station placement in Tower Shibuya, but that's not something that requires a major label's backing. He was recently featured on the cover of Sound and Recording magazine, a very prominent magazine but hardly directed at the masses of people buying records. It's hard to argue that the music itself is in tune with the "Japanese market" as a whole, since that's overrun with a pestilence of throwaway pop that seems, at least superficially, to be satisfying public demand.

This may have been one moment of a trend I would like to substantiate. What if, as the music industry as a whole declines (and it is declining in Japan, albeit more slowly than in the U.S.), artists who people are more deeply invested in decline less steeply than more disposable pop? What if owning an album like "James Blake" is more intimately tied up with identity creation than owning an AKB48 record? And of course, that's where my little hypothesis breaks down, because it's undeniable that the otaku gain a great deal of identity from their purchase (sometimes en masse) of AKB records and merchandise. The fact that it is inherently less valuable and interesting than James Blake, that these people are building their identities on sand, doesn't seem to make their activities any less persistent over time. In that context, the question shifts - we have to ask not, "What made this strange James Blake record successful?" but the rather more depressing, "What kept this excellent James Blake record from being a much, much bigger success?"

No comments:

Post a Comment