Note, 2013: Those with University Access can now read the fully-fledged article that came out of these ideas in Communication, Culture, and Critique.

|

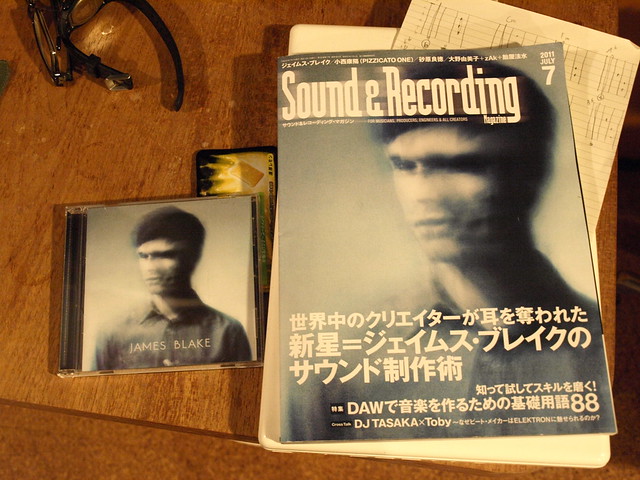

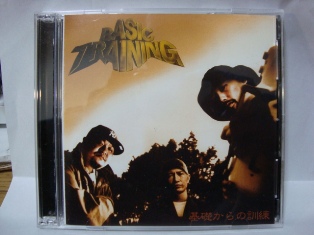

Image and some info from Mixtapetroopers

|

But in Japan the military connection is particularly deep and multidimensional, going back the better part of two centuries and connecting contemporary Japanese hip hop to the forces of Western imperialism and Japanese modernization. And "Basic Training" is specifically part of it. In his book Kokka to Ongaku [Nation and Music], Okunaka Yasuto tells the fascinating story of how the bakufu, the military government of Japan in the fading years of the Tokugawa Shogunate, came to introduce Western music to Japan for the first time (with the exception of missionary music that Christians had brought in the 15th century before their exclusion).

The motivation was not aesthetic - the introduction of the fife-and-drum corps was part of the bakufu's efforts to upgrade their military forces to modern standards of uniformity and organization. The Japanese military before the mid-19th century had their well-known equivalent of knights - the samurai - who mostly engaged in single combat on open fields or rode independently on horseback.. Then they had foot soldiers, who were decidedly not the equivalent of relatively well-organized English men-at-arms and bowmen. Rather, they tended to be utterly untrained and undisciplined peasants who ran around in chaotic masses. This was all well and good when they were fighting each other, but as soon as the bakufu became cognizant of the threat posed by the better-organized and -armed Western powers, they became quick students of modern military arts - or at least, to the extent that they could through the somewhat narrow channel of information they had access to, Dutch scholarship.

Along with technology (mainly guns), the bakufu realized they needed to adopt discipline, and this was strongly rooted in drilling and marching. There are some pretty fantastic scenes in, if I remember correctly, The Seven Samurai that suggest just how important the drum would have been to implementing uniform drilling. The townspeople that Takashi Shimura's character attempts to teach have a firmly ingrained habit of running at top speed and with no sense of unit cohesion when under the duress of training, up to and including running into each other.

|

| Shogunate Troops with Drum |

I found a trove of great information about this period over at Axis History (a site whose politics I know nothing about). The drum was introduced, along with other reforms, by Takashima Shuuhan, as a tool for management, giving marchers a guide for timing their step, regulating their speed, and in turn, staying out of one another's way. Here is a frame of drum scores from the book he released, and here's a great video of a contemporary troupe re-enacting what a pre-Meiji Japanese military band might have looked and sounded like:

This was, of course, a pivotal moment in Japanese history, of which the musical impact was among the smallest parts. But the link between music and militarism continued. Take, for instance, the so-called gunka, military or patriotic songs largely derived from the Prussian tradition (which replaced Dutch Learning as the basis for Japanese military practice in the Meiji era). And while the flowering of jazz in Tokyo starting in the 1920s was part of the strongly anti-militarist "Taisho Democracy," the groundwork for it was no doubt laid in part by the exposure to Western sounds that had started with Japan's military - particularly since military instruments were much closer to the sounds of jazz than the palette used in classical music, the other musical import aggressively promoted by the Japanese government as part of Meiji reforms.

But the biggest further impact of militarism on Japanese music came, of course, during the American occupation. During this time there were massive food shortages among the Japanese general public, and working musicians would certainly have mostly belonged to this group of the not-particularly-elevated. The only people with food and money in abundance were the occupying forces, so Japanese musicians quickly learned to play what the American soldiers wanted to hear - initially jazz, which they would have already understood well, and later early versions of rock and roll. The same dynamic continued into roughly contemporary times, though not in Tokyo - even today, the areas of Okinawa's capital city of Naha surrounding the American bases have clothing stores and music shops catering specifically to black American soldiers, forming a cultural resource for Japanese youth with any sort of interest in hip hop.

The bigger questions here are profound. I had long assumed that the story of Western music in Japan began with Admiral Perry's landing and the group of minstrels he brought with him, making the entire ensuing history of Western music in Japan a matter of imperial imposition. But this isn't the case at all - as happened again and again throughout Japanese history, something was consciously adopted from abroad as part of attempts to transform Japan into a nation that could compete internationally (that 'internationally' is complicated but key - at this point the Bakufu were reforming the military as part of a frantic rearguard action against international interference, so in some sense they were trying to keep from internationalizing - but were nonetheless doing just that). The same pattern would continue over the next century-plus, in music as in other things.